The Swine Health Information Center’s Standardized Outbreak Investigation Program (SOIP) includes a downloadable Word-based form and a web-based application to conduct standardized outbreak investigations. The program and tools were developed in response to an industry need for consistency in data collection and results across different investigators, outbreaks, and farms. Prompted and funded by SHIC, the web-based application has been available for nearly two years after development by program lead, Dr. Derald Holtkamp, Iowa State University, along with colleague, Dr. Kate Dion. Using aggregated outbreak information, investigators share herein detailed lessons learned through SOIP development and industry use.

In 2021, SHIC funded the development of the SOIP through a working group of 14 swine veterinarians formed to develop the terminology, approach, and instrument. In 2023, the tool was endorsed by the American Association of Swine Veterinarians Board of Directors for use in conducting outbreak investigations for swine pathogens. A web-based version for the standardized application was launched in 2024 with funding from SHIC, increasing the ease by which veterinarians can use and capture data from investigations in a secure database.

Outbreak investigations offer valuable opportunities to identify and prioritize biosecurity hazards. Dr. Holtkamp noted the saying, “Never let a good crisis go to waste.” While outbreaks are undeniably a crisis, they also present a chance to learn—though that learning is not automatic. When outbreak investigations are conducted comprehensively and systematically with the goal of identifying biosecurity hazards within the production system, they consistently generate insights that make the time and resources invested worthwhile.

SOIP Key Findings

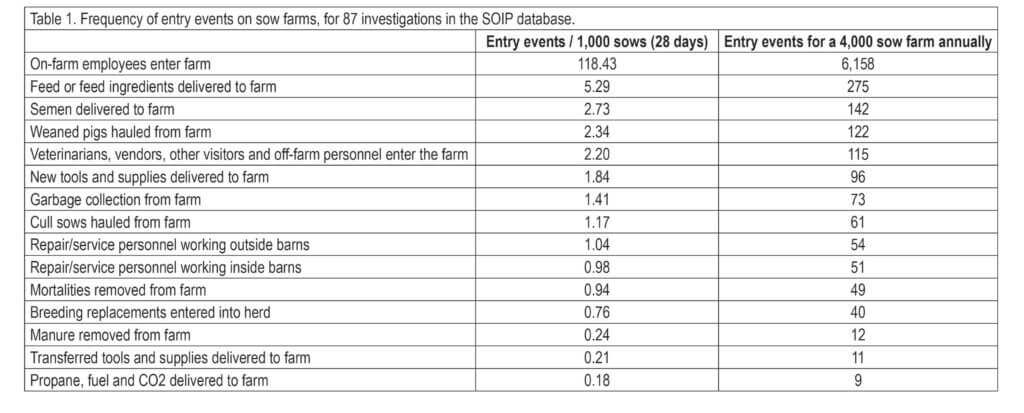

▪️Each entry event where a pathogen-carrying agent enters the farm poses a risk. Employee entry is the most frequent entry event (about 6,158 events annually for a 4,000-sow farm).

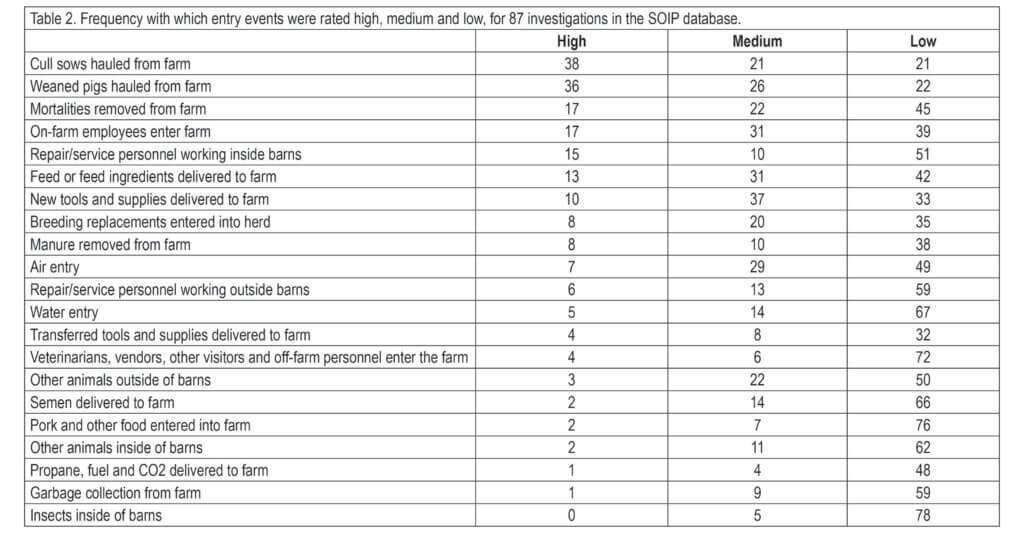

▪️Swine movements (cull sows and weaned pigs) were most often assigned a high hazard rating, followed by mortality removal, employee entry, and repairs inside barns.

▪️Outbreak investigations not only identify biosecurity hazards but also highlight systemic weaknesses in execution, planning, and monitoring. Industry-wide outbreak investigation data enables prioritization of resources to strengthen biosecurity.

Lessons learned from conducting outbreak investigations. As of October 2025, the SOIP database contained data for 87 completed investigations on sow farms across 24 different companies. Most of the investigations were done for PRRSV (n = 65) and PEDV (n = 19). The results presented here reflect all 87 investigations regardless of pathogen. While biosecurity risks vary by producer and farm, analyzing data at the industry level reveals where time and resources may need to be prioritized to strengthen biosecurity.

Frequency of entry events. Entry events occur when one or more pathogen-carrying agents, defined as something that can be infected or contaminated with a pathogen, enter the farm. Each entry event creates an opportunity for pathogens to enter the herd. The frequency of these events depends on herd size and the length of the investigation period. Some events occur continuously, such as air and water entry, while others occur periodically but are frequently unobserved, like rodents, wild animals, insects, and non-swine domestic animals. All other entry events on sow farms occur periodically and are generally observable. Among these, employee entry is by far the most frequent; each time an employee enters a barn, it counts as an entry event. On average, 118.43 employee entries occur per 1,000 sows over a 4-week period. For a typical 4,000-sow farm, this equals about 6,158 events annually (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of entry events on sow farms, for 87 investigations in the SOIP database.

Entry events rated high most frequently. A key component of the investigation is a subjective evaluation of how likely each entry event may be associated with an outbreak. This evaluation is based on information collected in the investigation form. Investigator(s) are responsible for making this determination and assigning a hazard rating of high, medium, or low to each entry event. Although an objective scoring system could offer advantages, a subjective approach allows investigators to weigh all available information within the broader context, including site location, season, weather conditions, and other factors that may influence the assigned hazard ratings.

Entry events most frequently rated high were swine movement events. Specifically, cull sows hauled from the farm received a high rating in 38 of 80 investigations where a rating was assigned, and weaned pigs hauled from the farm were rated high in 36 of 84 investigations (Table 2). The total number of ratings does not equal 87 for all entry events because ratings were not assigned when an event did not occur during the investigation period, and in a few cases, investigators omitted ratings even when the event did occur. Rounding out the top five high-risk entry events were mortality removal, on-farm employee entry, and repairs inside barns.

Table 2. Frequency with which entry events were rated high, medium and low, for 87 investigations in the SOIP database.

Lack of knowledge about the production processes. Biosecurity hazards originate within production processes, so identifying them requires a thorough understanding of those processes. Biosecurity hazards are often overlooked due to an incomplete knowledge of the production processes. Key details include: 1) procedural aspects (how tasks are performed, by whom, and when), 2) structural aspects (where tasks occur, including site and building layout and design), and 3) resource aspects (the tools and materials available to complete tasks). Many aspects of the production process are not fully understood by veterinarians or production managers, making biosecurity hazard identification challenging. This knowledge gap is even greater when critical activities are outsourced to third-party providers, such as livestock transport, loading crews, or manure removal. In fact, one of the most valuable outcomes of outbreak investigations is often the realization, “I don’t know, but I need to find out.”

Poor execution. Although biosecurity control measures are often well-intentioned, they frequently fail due to poor execution. Effective biosecurity requires getting the procedural, structural and resource aspects right, which frequently does not happen in practice. Use of chemical disinfection highlights these challenges. Personnel on farms or in truck washes frequently know which chemical disinfection to use and at what concentration, but it is rare that chemical disinfectants are applied at the intended concentration. They frequently don’t know how to dilute the chemicals (i.e., how many ounces to include per gallon of water), lack the proper equipment to do so, or apply the disinfectants incorrectly. A common example of the latter is to dilute the disinfectant that is poured into the injector well of a power washer. As it is applied with the power washer, it is diluted again at a rate that is seldom known, yielding the application of disinfectant with an unknown concentration that is likely much more diluted than desired.

No plans for rare or unexpected happenings. Weather, holidays, employee absences, equipment breakdowns, and urgent needs for supplies or equipment all occur on swine farms without exception. However, it is common to see these occurrences lead to significant biosecurity hazards. Just a few examples include equipment or supplies entering without any decontamination, repair personnel entering the site without showering in, and supplies urgently needed being transferred from other swine sites. These things happen because the production processes are built for the usual. Planning for the rare or unusual is often not done. The result is too many outbreaks where the unusual happened and the personnel on the ground dealt with it the best they knew how, but created biosecurity hazards that led to an avoidable disease outbreak.

Too little effort is spent on monitoring the process. Outbreak investigations are useful for identifying biosecurity hazards and if done systematically and relatively comprehensively, they can help identify critical control points. Critical control points are steps in the production process that are important for preventing outbreaks. For example, if trailers that enter a farm to haul cull sows also deliver them to cull markets or haul culls from other farms known to be positive for PRRSV or PEDV, then washing, disinfecting, and thoroughly drying those trailers between loads should be considered critical control points. We need to get them right nearly every time. For washing, we may want the removal of organic matter to be complete. For disinfection we may want the disinfectant applied at a desired concentration (e.g. 1:64). For drying, if done by TADD, we may want the surface temperature of the trailer to reach 160 degrees F and be maintained at that temperature for at least 10 minutes. Too often, these are left to chance. Nothing is monitored, no data is collected and there are no plans to periodically audit the processes to assure that the critical control points are being done consistently and correctly.

Industry encouraged to utilize SOIP. While each investigation provides valuable insights, a centralized database is essential for identifying patterns and learning from multiple investigations over time. The SOIP investigation database offers a unique opportunity to leverage the collective experience of the entire industry. The web-based application is available to all producers and veterinarians. Access to the application can be requested via email at [email protected].